After the Activision story, the tale of EA may sound kind of familiar – but its vastly amplified and simplified. When Trip Hawkins founded EA, he did it under the then-novel premise of an independent publisher; EA would run no internal studios, would produce no development of its own. Instead it would scout out, publish, and distribute the work of outside developers,

operating under the early Activision principle of promoting programmers and designers nearly as much as the games they developed.

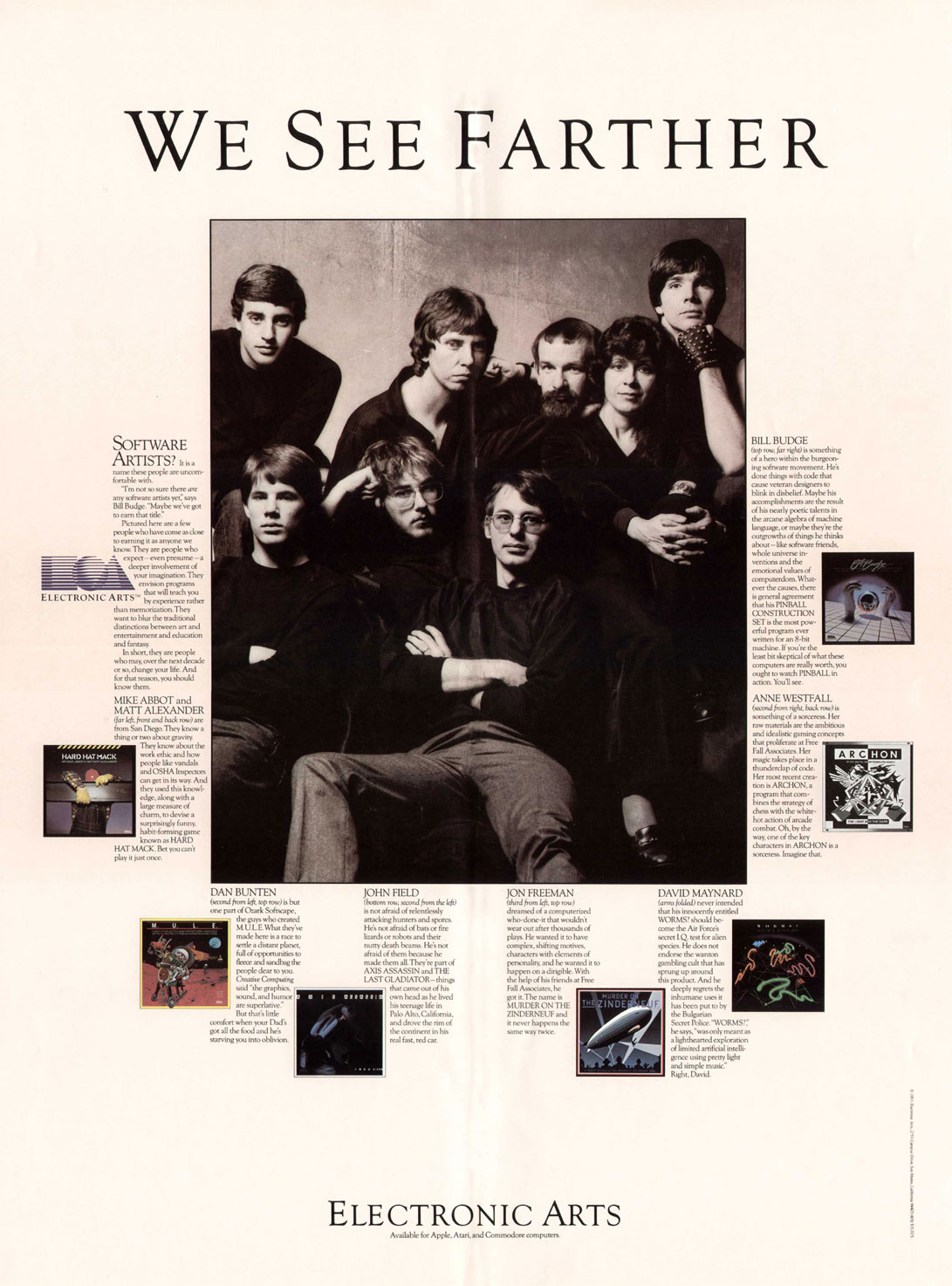

The name itself (based in part on United Artists) is telling; EA existed to proselytize the burgeoning art of electronic games; to act as a popular outlet for the voiced, yet scattered and unheard "software artists".

If anything, EA was positioned as – from a certain perspective – an improvement upon Activision's founding ideals, out record-labeling the record producer even down to the packaging. Whereas Activision served to broadcast the names and statements of its own – of the disgruntled superstars of bestsellers past – Trip Hawkins wanted to dig up new talent; to act as a sort of equalizer so your future Richard Garriots would have somewhere to turn. And hey, if those future talents happened to hit it off and make EA a bundle of money – then... well!

Indeed, EA started off well enough. In 1982, Hawkins left Apple Computer (formed in part thanks to Atari; see "Five that Fell" on this site), taking along several of his coworkers to staff his new venture. The initial plan, later put fully into gear by Larry Probst, was to sell directly to retailers – again an unprecedented idea – rather than work through a third party, the idea being that, as a professional conduit of other people's work, EA needed the best profit margins and market know-how in the business. The trade-off was that EA promoted its artists to the teeth and shared a large chunk of the profits.

Rispondi Citando

Rispondi Citando